The First International in America: A Cosmopolitan History

A version of this paper was presented at the Annual Conference of the American Historical Association in January 2023, and the International Convention of the Platypus Affiliated Society in April 2023.

After the dissolution of Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party in the late 1820s, Jeffersonian politics split. Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren’s party deployed Jefferson’s legacy to build a new form of “Democratic” politics, where the productive activity of the farmer and artisan took ideological primacy over commercial and financial expansion. However, Jackson’s true political ingenuity was his ability to present himself as the representative of Western farmers & urban artisans, all the while remaining faithful to Southern planters. Jefferson’s Party had strongly supported protectionist tariffs to encourage domestic manufacturing, but these were no longer politically viable if Democrats hoped to retain their base among the cotton-growing South. Appealing to northern artisans and Western farmers, Jackson’s Democrats eliminated property requirements for voting & political office while also promising greater access to land. Their political program for greater democratization helped maintain a tacit alliance between small farmers, urban laborers, and slaveholders under the leadership of the Democratic Party. On the other side of the split were Northern Jeffersonians & Paineites (after Tom Paine), champions of free labor, and leaders of the shorter-hours movement.

The split in Jeffersonian politics deepened in the political crisis of the Mexican-American War ––“America’s 1848,” when liberals were forced to confront the future of the republic: Would America extend the “Empire of Liberty”? Or would the republic establish the hemisphere for slavery? Would the war, as Horace Greely wrote, force “the world [to] recede toward the midnight of Barbarism”? This is how the crisis of liberalism presented itself in the United States.

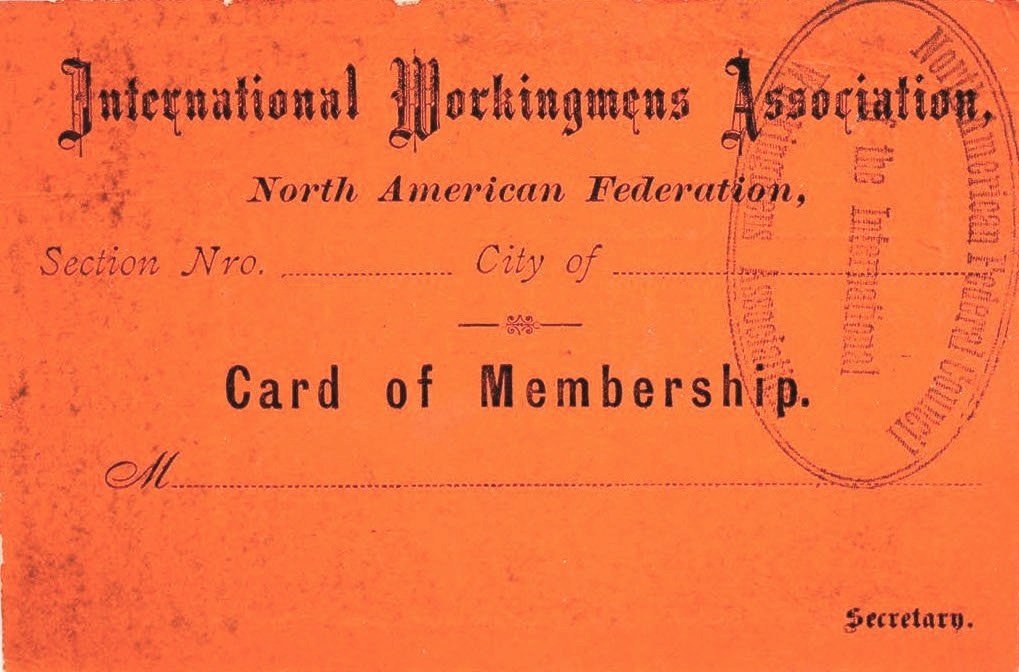

From the birth of the Republic onward, political ideas in America were cosmopolitan in nature. During and after the defeats of the 1848 revolutions, the American republic served as a shelter for a new generation of revolutionaries. This has led some scholars to label the arrival of socialist political ideas as “foreign importations,” at odds with the so called American “reform tradition”. The label is misleading. Throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries, Europe’s republicans promoted the ideals of the “Transatlantic Republic” as their own, they drew from the egalitarian values of the Rights of Man, the Declaration of Independence, and early American Paineite societies. German reformers wrote biographies of the Founding Fathers; British Chartists incorporated the American flag as a guiding symbol in their meetings; and trade-union leaders and socialists in London doubled down against the affront on free labor during the American Civil War by founding the International Workingmen’s Association. Once revolutionaries & reformers landed in the United States, they thus brought back to Americans concerns about the future of liberty, which had their origins in the republic’s founding. In the early fights for a shorter working day in the US, for example, the Chartist ex-pat John Cluer (a leader in New England circles) called for a “Second Independence” by American workingmen. In the American Civil War, one tenth of the entire Union Army were German born. Once the First International reached the United States, in 1869, four out of the seven New York City labor unions were German. Needless to say, that the so-called “German problem” in America, was a fundamentally American problem, since it displayed one of the main features of the United States, as a nation of nations––the site of the World Republic (Paine).

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, the Southern attack on free labor was denounced across European labor circles as a step backwards from the aspirations of eighteen-century revolutions. The working men of Britain rallied behind the Union cause, alongside French, German and American reformers. From 1862 onward, British workers engaged in meetings and mass protests to mobilize public opinion against Prime Minister Lord Palmerston’s bellicose plans to support Confederate “independence.” Cooperative reformers founded “Emancipation Clubs” to rally labor’s support for the North, and social democrats wrote furiously in the labor press against what German exile Karl Marx called the “criminal folly” of the ruling classes. Speakers at these packed meetings included abolitionists and Chartists, as well as influential liberals such as John Bright, black Americans like J. Sella Martin and leading Garrisonians Mary & William Craft. The Union Emancipation Society brought together textile workers and abolitionists to lead the political opposition against Southern rebels, at a time when the established British anti-slavery forces failed to do so.[1]

This transatlantic solidarity inspired the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA) on 28 September 1864. By October 1865, the IWA had “[given] the American flag the place of honor” at their meetings to celebrate that “Democracy had triumphed, slavery had perished,” and “the republic was saved.” As they understood it, “the flag, which had for been so often insulted by the privileged classes of Europe, will yet proudly wave throughout the world, the emblem of liberty and the hope of the oppressed.”[2]

Black troops in the Union Army

The American Sections

Twenty-three English trade unions representing upwards of 50,000 total members formed the First International’s core.[3] Its founding coincided with the rise in trade union activity in the 1860s, in both the United States and Europe. The first enduring, nationwide labor organization in the United States was founded in 1866, the National Labor Union (NLU), which the International called “the most advanced practical advocates of the rights of labor in America.” The NLU had a peak membership of 300,000, among them was First International leader and Baden revolutionary Friedrich Sorge.[4] In London, the General Council followed the activities of the NLU and established lines of communication with officers William Sylvis, president of the Iron Molder’s International Union and tireless advocate for the eight-hour day, and William Jessup, the corresponding secretary for the most powerful trade union body in the country, New York City’s Workingmen’s Union.[5]

Sylvis had established a common alliance with Lassalleans in the National Labor Congress of 1867, when he introduced a resolution calling for the US Congress to appropriate twenty-five million dollars “to aid in establishing the eight-hour system.” Sylvis defended the proposal against criticism with the support of several German members. During the following year, he called for the establishment of a federal Department of Labor to distribute public land, regulate trade unions, and promote cooperatives. When members challenged his motion, Sylvis argued in favor of the Lassallean Prussian model: “[I]n Prussia they have a Labor Department, presided over by one of the ablest men of the day. The working class has the arm of the Government… around it, and are properly protected.” For both Lassalle and Sylvis, the “people’s state” was a permanent feature of a liberated society. The official affiliation of the NLU with the IWA was cut short, in part due to the sudden death of Sylvis.

Outside of the NLU, the IWA lacked the deep connections to trade-union circles that it had in England. American efforts leaned heavily on the German Forty-Eighters, Friedrich Sorge and Siegfried Meyer. German immigrants made up about half of the total membership of the International in America. In 1869, Sorge became the spirited leader of the first section in America. In addition to members from their defunct Communist Club, Sorge and Meyer sought to bring together Lassalleans, former members of the General German Workers’ Association (GGWA), as well as anti-Lassalleans from the N.Y. Arbeiter Union.[6] This period of social democratic unity among German immigrants had formed the basis for Section 1, but in 1870 the Franco-Prussian War split the immigrants. Many of its members defended Bismarck’s war on the basis of national unification. By publicly opposing the war, the IWA lost its connection to the larger German workers’ movement. This turn of events, combined with the decline of the NLU in the 1870s, resulted in the isolation of the IWA from its ideal audience: the American working class, both English and German-speaking members. The mass anti-war meeting did, however, significantly raise its profile among American-born citizens and incited curiosity from veteran land reformers, communalists, and Free Love radicals, who were also in attendance at Cooper Union’s anti-war demonstration. In the months that followed, many of them joined the International as new English-speaking sections.

The American English-speaking faction, which eventually battled Sorge for leadership of the IWA, was spearheaded by prominent republican reformers William West and Victoria Woodhull, whose departure from the North American Central Committee resulted in the formation of two rival “Federal Councils” on 19 November 1871. Woodhull was an early supporter for women’s rights, spiritualist and free lover, who gave the opposition its voice on the pages of her paper, Woodhull & Claflin Weekly, the first newspaper in the United States to print an English translation of the Communist Manifesto.

Before 1871, Woodhull had called herself the nation’s “First Lady Broker,” an influential spiritualist, proud Free Lover and women’s rights advocate, but not a labor reformer. Her trajectory into the International was aided by her mentor Stephen Pearl Andrews, an eclectic antebellum abolitionist and founder of the mystical Free-Love society, “The Pantarchy.” Andrews was influenced by Fourierist ideas but landed in New York’s early anarchist circles around Josiah Warren.[7] Through his lectures and writings, Andrews popularized Warren’s ideas of “Individual Sovereignty,” the belief that each human being was the only authority on his or her true sexual relations. In 1851, Andrews and Warren co-founded the social experiment of “Modern Times,” which was frequented by émigré revolutionaries connected to the Universal Democratic Republicans (UDR)—among them was the English Garibaldian and spiritualist Hugh Forbes. In lively debates and public events, members discussed ideas of socialism, Free Love, and greenbackism. As Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz’s has described it, Andrews’s “odd combination of anarchic liberalism and economic radicalism” left a deep impression on Woodhull’s political imagination.

In December of 1871, the English-speaking International Sections 9 and 12 successfully organized a procession in honor of General Louis Rossel, a military hero of the Commune who had been recently executed by the Thiers government. Escorted by new Parisian refugees, the march featured a horse-drawn coffin, draped in red and displaying the words “Honor to the Martyrs of the Universal Republic.” Several thousand walked alongside Broadway Avenue, including the black militia unit, the Skidmore Light Guard; a band of Irish republicans; Cuban political refugees; French, German, Swiss, and Bohemian Sections of the International; and a band of American women, led by the sisters Tennie Claflin and Victoria Woodhull, who carried a red flag with the inscription, “Complete Political and Social Equality for Both Sexes.”[8]

Ideological tensions within the U.S. Sections grew from arguments over the meaning of the “social republic of labor”. The American split was shaped by the aftermath of the Paris Commune (1871). While the Commune took the International from relative obscurity into mass notoriety, it also exacerbated tensions among the General Council in London. Its vigorous campaign for the recognition of the Commune prompted the first break in the leadership (GC), with two members stepping down from the Council after the publication of Marx's Third Address on the Civil War in France (a text commissioned by the leadership). Among London’s leaders, the old Chartist and influential trade unionist, George Odger sided with liberal reformer Charles Bradlaugh in a “Republican campaign” supporting the Versailles Republic against the Communards. Preceding the Bakunin-Marx split, the break over the Commune in the organization had a destabilizing effect at the center of the IWA’s organizational life. In effect, the Paris Commune created a clear fissure within the IWA on the question of working-class political power, but along an existing fault line. That is to say, the Commune brought forth a problem which had remained hidden from view. It is worthy of note that the American split took place after the Commune, when the International was already under significant pressure to clarify its political ends. It was the break over the Commune which was at the center of the IWA’s demise.

Communards' Wall at the Père Lachaise cemetery, where one-hundred and forty-seven Commune soldiers along with another nineteen officers were executed on May 28, 1871 during the Semaine sanglante, the suppression of the Paris Commune.

Although the disagreement with labor republicans in England was an ocean away, the American strife between Woodhull’s Section and Sorge’s faction originated from a similar predicament. That is, from a fundamental ambivalence toward forging the independent political power of labor, in a country where workingmen had the vote.

As in Europe, within the United States there were significant differences in interpretation regarding the political power of labor. However, these differences did not correspond to divisions between German and American Sections. On the contrary, we find upon a closer inspection that, within the American Sections, members offered contrasting plans for political power. Victoria Woodhull (Section 12) and her plan for an Equal Rights Party that could promote “the equal civil and political rights of all American citizens regardless of sex,”[9] was an entirely different proposition than C. Osborne Ward’s (Section 9) call for a Labor Party, that is, “a party of workers… based upon the wants of workingmen.”[10] On the issue of labor leadership, Woodhull was closer to her ally William West (Sec. 12), who argued for the leadership of educated reformers over workingmen. Ward, for his part, wrote explicitly in his 1870 pamphlet, “The Great Labor Party,” that while “reforms are all necessary… they do not constitute the Labor question,” and since “Labor Progress originates in the Laborer,” then “It is a great error to suppose that this movement obtains its impetus from the middle class.”[11] While West and Woodhull imagined a party where reformers could fight for a variety of causes, including equal rights for women, free love and spiritualism, Ward called for a singularly-focused political party, where workingmen could “work freely for themselves” to advance “toward the great ultimatum of Social Revolution.” While the change in labor relations were central in Ward’s plan, priority was given to the transformation of government—what Michel Cordillot has called the “democratization” of the state. In other words, constitutional reform in government was seen as the necessary lever for, and precondition of, the social revolution. Once the referendum was in place then all of “the management of business in all its productive and distributive ramifications” would be “deliver[ed] to the state, or rather to the people through the state.” Thus, first, the American laborers had to wrest governing power from the monopolists and drones with a “Great Labor Party,” since, according to Ward, the “the rich cannot accomplish proletarian reform.”[12]

In her newspaper Woodhull, defended the democratic republic against the social revolution and argued that workingmen should deploy “the power of the Almighty Ballot” against monopolists in power.[13] “The fault…” she argued “[lies in] the Constitution — and the laws of the country which allow for such a usurpation of power to take place.” The American faction thus echoed the early Chartist formulations about constitutional change and representational “justice” in government, which had been opposed by London radicals like the Chartist Joseph Harney—Marx & Engels’ associate in the 1830s and ’40s. Woodhull’s faction published an “Appeal” in the Weekly where they argued that the primary task of the International was the expansion of political participation so that all citizens could take part “in the preparation, administration and execution of the law by which all are governed,” which would justly deliver industry back to “the people through the state” under a “new government.”[14]

In correspondence with Sorge, Engels wrote that “it was not the task of the International to shift the foundations of the existing state but, rather, to exploit it.”[15]The IWA should not “perfect” the democratic republic but, rather, abolish the external compulsion of capital on political action. The International, argued Sorge, “is and ought to be a Workingmen’s organization—nothing else.” He called on the General Council to introduce a resolution which would admit new Sections only “when at least two thirds of their members are wage-laborers,” resulting in a minority of middle-class members in each section. When Sorge’s faction unfavorably compared “middle-class” to “working-class” reforms, they were making a political judgment, not a sociological one. The distinction lay in whether or not reforms advanced the democratic control of industry by workingmen. “Middle-class reforms” would make capitalist class rule more inclusive at the expense of labor’s political independence. These were the lessons of 1848, a return to the problem of Bonapartism. A workers’ state as Marx wrote of the Paris Commune for the General Council, was “the political form… under which to work out the economical emancipation of labor.”[16] The original IWA mandate was for workingmen to “conquer political power” in order to lead the democratic discontent in society. While, in the first years of the organization, this mission remained purely theoretical, the Paris Commune brought latent disagreements to the forefront. The international split on this critical point.

When Mikhail Bakunin argued that national branches should act autonomously from the General Council, the American opposition was decidedly in support of Bakunin solely on the principle of federalism. Their call for autonomy resounded with key members of the organization, including the former IWA General Secretary John Hales, who had corresponded with the American opposition without reporting to the GC. Like Section 12, Hales was also in profound disagreement with the autonomists on the question of political action, but he aimed to secure the independence of the British Federal Council from the organization’s leading body.[17] Without belaboring the point here with too many details about the conflicts plaguing the IWA back in London, it will suffice it to say that beneath the so called “autonomist” vs. “centralist” disputes, were profound disagreements on the very nature of the International. Rather than a rejection of “authority” in the abstract, many of those who aligned themselves with the Bakunin faction did so in order to break from specific mandates given by the Council. In other words, these members of the opposition held political disagreements with the GC which remained largely unelaborated under a nonspecific demand for “autonomy.”

Given what we know of the plans by Section 12 to forge a new party, it may be curious to learn that these Americans aligned themselves with the “autonomist” (or “anarchist” faction) against the “centralists” (or “Marxists”) during the final split. Unlike Bakunin’s anarchists, the American opposition did not reject political action or aim to “destroy the state” (Bakunin). On the contrary, both Woodhull (Section 12) and Ward (Section 9) hoped to create an “activist” state through constitutional reforms. Ward’s plan went even further, insofar as he argued that the worker had to seize the state, either through democratic or revolutionary means, and that a labor government could be used as an “instrument” to tackle the social problem. Woodhull and West, on the other hand, saw the extension of formal equality and constitutional reform as the ends of the Equality Party. While not in line with the anti-political claims of the Bakunin faction, Section 12’s alignment with the autonomists was driven by their insistence that it was “the independent right of each section” to “[interpret] freely… the decisions of the Congress, the statutes and ordinances of the General Council,” and, moreover, that “each section [was] responsible for its own conduct.” This challenge to the General Council was a direct rejection of the organization’s authority and led to the final expulsion of the Section.

IWA disbanded on the 15th of July 1876—its headquarters had been moved to NYC in 1872—by then, it was a shell of its former self. Sorge continued his fight well into the late 1870s, when the Marxists in America slowly won over the Lassalleans and the two sides reconciled on principles similar to the ones that united the two groups back in Germany at the Gotha Congress of 1875. But this too was short lived. Sorge along with the former Irish Secretary of the International, J.P. McDonel broke off from Lassalleans. They left the joint venture of the Workingman’s Party of the United States, because the Lassalleans successfully pushed for electoral collaboration with the Greenback-Labor Party. So Sorge & his supporters joined the American eight-hour-day reformers, Ira Steward and George E. McNeill—a leader in the Knights of Labor. Together they founded the International Labor Union (ILU), an “organization of all workingmen” under the “National and International amalgamation of all Labor Unions.” Clearly, this was a concession – a step backwards from the calls for political power which were at the forefront of the Inaugural Address. Perhaps it was a step back in order to move forward. Amidst the political decline after the IWA, Sorge, along with Marx, regarded Steward’s ideas as “an oasis in the desert of currency reform humbug” which had overtaken the Lassalleans. Steward and McNeill were especially taken by a copy of Marx’s Capital. After reading it, Steward had nothing but praise for the chapter on the working day and wrote Sorge that he wanted this “translation of Karl Marx to be read.” He found a common ally in Sorge. In his letters, Steward wrote that the Lassallean opposition which Sorge had faced all these years was, “made up of the same middle-class reformers that he’d been fighting, for the past ten years in New England.”

A Common Understanding: Class Society

In 1875, when textile workers went on strike in Fall River, Massachusetts, the Boston Eight Hour Leaguers joined with the Marxists once again to raise a strike fund. In the final days of the strike, the Massachusetts militia was called out to suppress the strike, and were successful in stopping the workers from marching to city hall. This confrontation left a profound impression on Steward, who saw with his own eyes the reality of class society in the United States. He incorporated his insights into the “Resolutions of the Boston Eight-Hour League” (1876), where he wrote that the manufacturers “and their operative classes are living in war relations with each other.” Since no investigation had followed the militia intervention, he concluded that “the Capitalist classes and the State authorities are a unit in all that concerns labor.”[18] While earlier in life he had been in vehement opposition to strikes, his disappointing experience with legislative reform and political campaigns had moved Steward to consider alternative means to achieve the emancipation of labor.

Steward admitted that he was surprised to read that Karl Marx had heard of Eight-Hour League, since he was “ignorant that any one abroad was observing and sympathizing with us.” Once in touch with the Marxists, Steward was impressed by the work of McDonnell and Sorge, going so far as to say that, under McDonnell’s editorial leadership, the New York’s Labor Standard was “the most important fact now existing to us labor men.” When Lassalleans threated McDonnell’s position in New York, Steward personally helped him move the Labor Standard to Boston. He also praised the WPUS’s declaration of principles, which in his assessment represented “far in advance of any thing ever before adopted by labor men.”[19] Steward did not shy away from voicing his critique of items on the platform, but he recognized that both groups ought to work together given their essential commonality in principles. To the New England reformer, Sorge had arrived as an answer to his dreams and prayers for the labor movement.[20] As their relationship developed, the two reformers also developed a close friendship.[21]

The shared understanding between Sorge and Steward arose from a common social concern, rather than a cultural or national bond. While Steward made apparent in his letters to Sorge that he was unaware that anyone outside of United States had taken note of his efforts, he was happily surprised to read Marx’s account of American struggles for the shorter-working day in Capital and found clarity in “the Doctor’s” theoretical insights. But most importantly, Sorge and Steward’s practical alliance was built on their shared perspective that middle-class reform campaigns threatened the emancipation of labor.

At the most elementary level, both Sorge and Steward agreed that the first task facing labor was the independent organization of working people into trade unions, rather than their blind mobilization to the ballot box. This alone was enough to create the conditions for collaboration between the two reformers. They both faced the same task in practice and shared a critique of the existing obstacles to their success.

Steward was not the only one to find new allies among the German socialists. After his stint in the International, Section 9’s C. Osborne Ward reconnected with the German Lassalleans around New York’s The Socialist and became an organizer for the Socialist Labor Party. While supportive of the party’s work, Ward remained a critic within the organization, arguing in 1876 against the “wretched hacking under the guise of co-operation and currency reform,” which he wrote provided “nothing in its propositions.”[22] In addition, DC’s Section 26, Richard J. Hinton became a journalist for the Socialist Labor Party. In the late 1890s, Hinton worked as the chief of the colonization commission for Eugene Debs’s Social Democratic Party of America (f. 1899).

Steward and Ward are exemplary figures of the American Left—their experience with abolitionism, cooperatives, and democratic societies makes them especially qualified representatives of the American synthesis taking place at the end of the nineteenth century. However, unlike Woodhull and West, who found in Sorge and his supporters nothing more than “sect of ignorant aliens,” unable to connect with American society, the two found a common calling with immigrant German socialists—both Lassalleans and Marxists. Their trajectory shows us that perhaps the most salient feature of American labor reformers was their capacity to think beyond the narrow limits of a national politics. Within the debates and organizations for the emancipation of labor, these labor reformers were integral in the transatlantic debates of social democracy.

[1] The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS) denounced Lincoln’s emancipation and attacked the Union. An excellent account of this astonishing episode in British abolitionist history is in James Heartfield, The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 1838–1956: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 149–172.

[2] “International Working Men’s Association Soiree at St. Martin’s Hall,” The Workman’s Advocate, 7 October 1865, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Civil War in the United States, 3rd ed. (New York: International Publishers, 1961), 185.

[3] At the IWA’s peak in 1867. See “Appendix 2: Membership” in F. Bensimon u.a. (Hrsg.): “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2018), 387–88.

[4] On the eve of the 1873 (peak membership). In addition to northern industrial workers, its ranks featured southern workers; black labor leaders, women workers, including the ship caulker Isaac Myers from Baltimore; a contingent of German unions and organizers.

[5] The NLU’s initial program spelled out that unions should “help inculcate the grand, ennobling idea that the interests of labor are one.”

[6] Historical accounts of the Allegemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein (General German Workingmen’s Association, GGWA) in the United States vary considerably. According to S. Bernstein, the organization was founded in 1865, while M. Hillquit records its founding in 1868, and P. Foner argues that it emerged in 1866. The organization is not to be confused with the earlier Allgemeiner Arbeiterbund, founded with the help of Christian socialist émigré, Wilhelm Weitling in October 1850. Historians writing about the IWA have used the name “General German Labor Union” to refer to the “Allegemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein,” see for example Timothy Messer-Kruse, The Yankee International, 73. However, the word “Verein” or “association” carried a distinct meaning, marking the organization’s independence from trade unions. It is important to keep this in mind for this particular organization made up of Lassalleans, who were opposed to trade unions and advocated workers’ cooperatives with state aid instead. The translation of the “Allegemeiner Deutscher Arbeiter-Verein” into “General German Labor Union” seems to date as far back the Philip Foner and Chamberlin 1977 edition of Friedrich A. Sorge’s Labor Movement, translated by Brewster Chamberlin and Angela Chamberlin. Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States (5th ed.) (New York: Russell & Russell, 1965), 163–180; Philip Foner and Chamberlin (eds.), Friedrich A. Sorge’s Labor Movement in the United States: A History of the American Working Class from 1890 to 1896 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1977), 9; Samuel Bernstein, The First International in America, (New York: A.M. Kelley, 1965), 37. For further clarification on the Allgemeiner Arbeiterbund see Eric Arnesen, Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History (Volume 1), (New York: Routledge, 2007), 511–12. I owe this clarifying note to Philipp Reick in “Labor is not a Commodity!”: The Movement to Shorten the Workday in Late Nineteenth-Century Berlin and New York (Campus Verlag: 2016).

[7] Josiah Warren was the mentor to the American anarchist Benjamin Tucker (1854–1939). See Josiah Warren Papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center); and notes on Josiah Warren (box 32) in the Agnes Inglis Papers in Labadie Collection. There is significant overlap between Warren and German anarchist thought, see Max Stirner, The Ego and its Own: The Case of the Individual against Authority (1844) tr. S. T. Byington (London and New York, 1907).

[8] Descriptions of the parade, on 17 December 1871, can be found in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, December 30, 1871, pp. 243, 247, and January 6, 1872, pp. 263–65, including an illustration of the parade; The Day’s Doings 6 January 6, 1872 also includes an illustration.

[9] “Equal Rights Party Platform” (1872).

[10] Osborne Ward, “The New Idea: Universal Co-Operation and Theories of Future Government” (New York: The Cosmopolitan Publishing Company, 1870), 11.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid; Ward “The Great Labor Party,” 1–2.

[13] Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, 23 November 1871

[14] Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly 23 September 1871.

[15] “Also nicht die Grundlagen des bestehenden Staates umzuwälzen, sondern ihn auszubeuten war hiernach der Beruf der Internationalen” F. Engels, “Die Internationale in Amerika,” written July 9, 1872. First published in Der Volksstaat, No. 57. July 17, 1872.

[16] Marx, Civil War in France.

[17] Hales had broken with Marx and Engels on the Irish question. He demanded the dissolution of independent Irish sections (May 1872) which he wanted to subordinate under the British branches. But Marx worked closely with Irish radicals like the Fenian, J.P. McDonnell (International Secretary for Ireland) and had hopes that the Irish workers would help to advance a much-needed revolutionary perspective, and to push against the moderate tendencies of English workers. Subsuming the Irish workers under English trade-union leadership would squander this opportunity. In the minutes of the GC, Engels argued that the Irish constituted a nation, and so should be incorporated into the International like other national branches. Hales’s proposal to dissolve the Irish branches was defeated by 22 to 1. Hales continued his mission to create an autonomous British Federal Council and made a final break with Marx at the Hague Congress (1872), siding with the Bakunin faction on the basis of national autonomy from the General Council. Documents of the First International, 1871–1872, 205–208.

[18] “Resolutions of the Boston Eight-Hour League” (1876) in Ira Steward Papers.

[19] Emphasis in original, Steward to Sorge, 4 December 1876 in Ira Steward Papers.

[20] Steward to Sorge, 1 March 1, 1877 in Ira Steward Papers.

[21] Steward wrote, “how warm I feel to you[,] you will never realize” Steward to Sorge, [n.d.] in Ira Steward Papers.

[22] C. Osborne Ward, “Individualism vs. Socialism,” The Socialist (27 May 1876)