The First International in America: A Cosmopolitan History

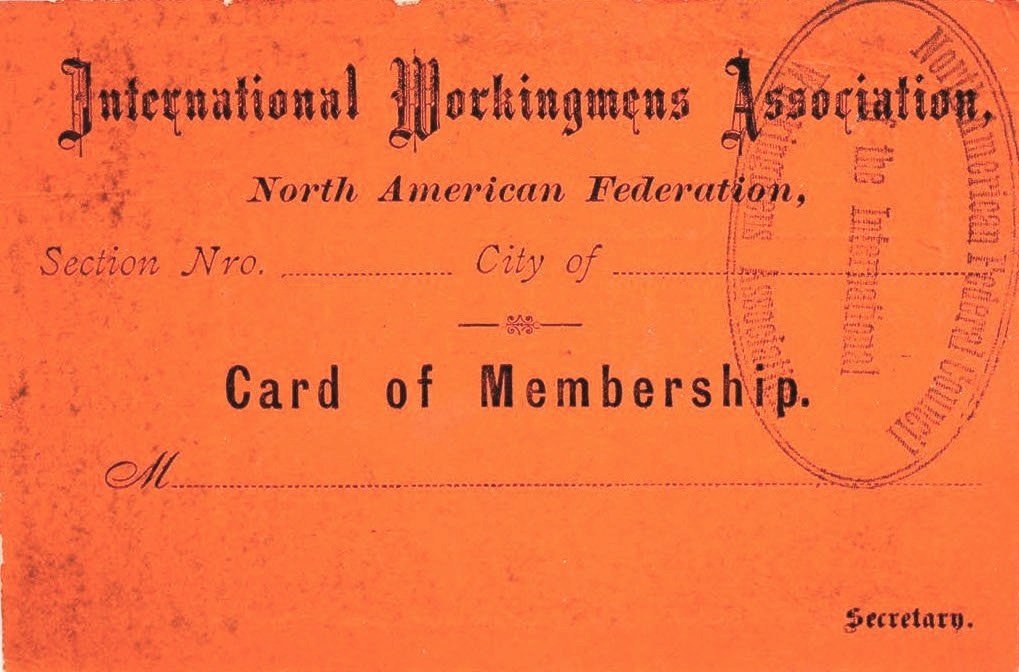

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, the Southern attack on free labor was denounced across European labor circles as a step backwards from the aspirations of eighteen-century revolutions. The working men of Britain rallied behind the Union cause, alongside French, German and American reformers. From 1862 onward, British workers engaged in meetings and mass protests to mobilize public opinion against Prime Minister Lord Palmerston’s bellicose plans to support Confederate “independence.” Cooperative reformers founded “Emancipation Clubs” to rally labor’s support for the North, and social democrats wrote furiously in the labor press against what German exile Karl Marx called the “criminal folly” of the ruling classes. Speakers at these packed meetings included abolitionists and Chartists, as well as influential liberals such as John Bright, black Americans like J. Sella Martin and leading Garrisonians Mary & William Craft. The Union Emancipation Society brought together textile workers and abolitionists to lead the political opposition against Southern rebels, at a time when the established British anti-slavery forces failed to do so. This transatlantic solidarity inspired the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA) on 28 September 1864. By October 1865, the IWMA had “[given] the American flag the place of honor” at their meetings to celebrate that “Democracy had triumphed, slavery had perished,” and “the republic was saved.” As they understood it, “the flag, which had for been so often insulted by the privileged classes of Europe, will yet proudly wave throughout the world, the emblem of liberty and the hope of the oppressed.”

Marx after Marxism: An interview with Moishe Postone

Moishe Postone is Professor of History at the University of Chicago, and his seminal book Time, Labor, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx’s Critical Theory investigates Marx’s categories of commodity, labor, and capital, and the saliency of Marx’s critique of capital in the neoliberal context of the present. Rescuing Marx’s categories from intellectual and political obsolescence, Postone brings them to bear on the global transformations of the past three decades. In the following interview, Postone stresses the importance of an analysis of the history of capital for a progressive anti-capitalist Left today.

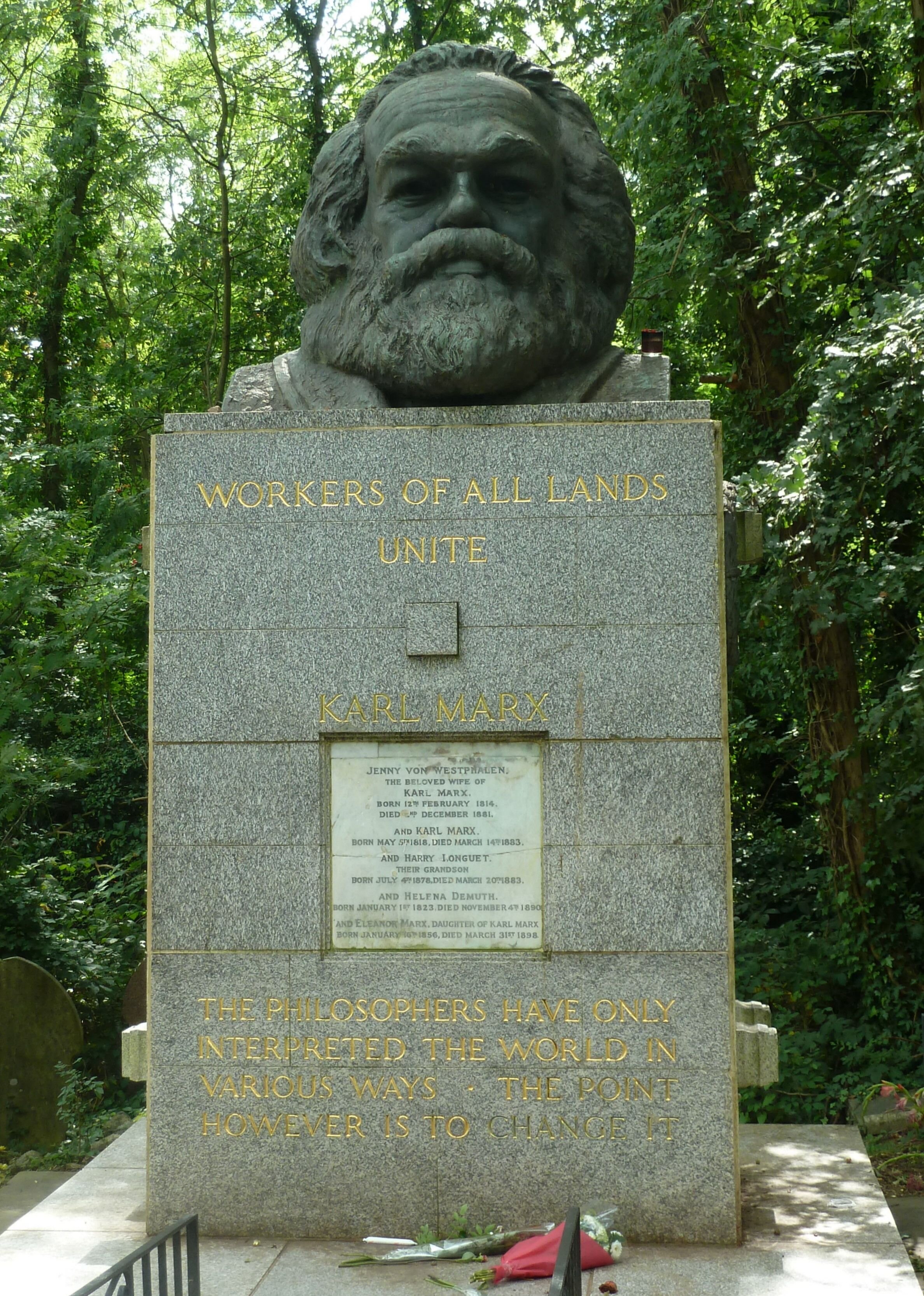

Monumental History

Confederate statues were erected across the South in the early twentieth century, when Southern politicians were revising the history of the Civil War. They aimed to transform this chapter of American history from an emancipatory struggle into a Confederate defense of “states’ rights” led by a valiant race. Unfortunately, this Southern propaganda has survived the twentieth century. On the American citizenship test there remain two “correct” answers to the question, “What caused the Civil War?”: “slavery” and “states’ rights”. Despite this propaganda, every Confederate statue today remains a testament of the slaveholders’ defeat. Each one is a reminder that the Confederacy lost the war. What good we make of the victory of free labor over slavery is yet to be seen. But one thing is certain: nothing good will come out of forgetting the Civil War.

Helplessness without history: Political education after the Millennial Left

What follows is an edited, revised and expanded version of a teach-in given on Moishe Postone's 2006 essay “History and Helplessness” and the origins of Platypus, given on November 9th, 2023, at the University of Chicago.

The Cancel Wars: The Legacy of the Cultural Turn in the Age of Trump

Today, anti-civil society revenge fantasies under the guise of “justice” provide an outlet to the hopelessness and despair festering after the 2016 election of Donald J. Trump. In this new public discourse, “blackness” is to be protected from appropriation, female sexuality is a passive victim to a pathological male sexuality, and we must all fight the bigoted cis-white male cop inside of us. But this unseemly Twitter reality offers little for emancipatory politics. Like in the election of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, the Left is once again looking for culprits and finding it in the bigotry of the voting public.

Review: The People v. O.J. Simpson

As The People v. O.J. Simpson artfully pieces together, in the 1990s, O.J.’s acquittal provided the semblance of racial justice by eliciting a feeling of victory through the spectacle of a televised trial. This dose of self-delusion was delivered in bleak times in America, especially brutal if you were poor and black. Vanity Fair’s Dominick Dunne—featured in the show as the wealthy, but culturally-conscious, New Yorker—wrote in 1997 that the O.J. trial had something for everyone: “love, lust, lies, hate, fame, wealth… the bloodiest of bloody knife-slashing homicides,” and “all the justice that money can buy.” The verdict was all the justice a black man in America could buy in 1994—if he could afford the price. However, The People v. O.J. Simpson suggests that there may have been a greater cost: this judicial victory was gained by peddling a false promise of redemption to working black Americans.

Lessons Learned from the Death of the Millennial Left

Occupy erupted in 2011 after the revolt of the Tea Party, a populist expression of discontent from the Right which provoked a renewal among the Republican Party base. In the shadow of the economic downturn, amidst global austerity protests, the Zuccotti Park occupiers looked to the rebellions in Cairo, Tunis, Athens and London. They were inspired by the forms of organization and mobilization at Tahrir Square and the popular assemblies in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol but directed most of their discontent against the government bailout. After NYC, copycat protests spread to hundreds of cities, on every continent — it was an explosion otherwise unprecedented in my lifetime, a spontaneous expression of popular discontent that cut across the political spectrum.

Two Steps Back

Not unlike the late 1950s, students today find most compelling in Marx what among the existing Left is fraught with a great deal of ideological confusion: the possibility of historical transformation. And though we can write and rewrite about the centrality of the eleventh thesis of Feuerbach until pages are worn to a pulp, in truth, we insist on the relevance of this line precisely because society has proven so recalcitrant to change—from the Left. “Crises” are no longer opportunities for political mobilization but just reaffirm how powerless the Left is, even in the face of economic collapse. Presently, the Right is much more effective at organizing in times of social discontent and holds the monopoly on the rhetoric of freedom—once the battle cry of the Left. We have reached an historical impasse of great political consequence. In the face of this degeneration, how do we assess whether or not any self-purported Left either by “carrying on” with the political “struggle” or by returning to “the legacy of socialist thought,” is actually working towards social revolution? Writing amid the sound and fury of the Cold War, Mills was plagued by a sense that both the Right and the Left had become obstacles to transformative possibilities. As a critic of the Left, Mills leaves much to be admired. It is through this framework that his “Letter to the New Left” (1959) can speak to us today.